Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common eating disorder in the United States with an estimated 1-2% of the population being affected. Although it’s been around for a long time, it was only recognized as an eating disorder and added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 2013. Binge eating disorder is characterized by eating a large amount of food in a discrete period of time, and feeling a loss of control while eating. Some people also experience eating more rapidly than normal while binging, or eating until uncomfortably full, even when they weren’t hungry to begin with. Additionally, it may include feelings of guilt, shame, and embarrassment. Regardless of how the criteria are met, significant distress regarding binge eating is usually present.

BED differs from bulimia nervosa in that it is not associated with the regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviors such as vomiting, restricting intake, or excessively exercising. With that being said, people with BED may still engage in these behaviors on occasion.

Risk factors for BED, like all eating disorders, vary. There is evidence that genetics as well as environmental factors play a role in increasing one’s risk of BED. Having a history of mood disorders in the family, abuse or trauma, or growing up with people who have disordered relationships with food, such as friends or family, may all influence the likelihood of someone having BED.

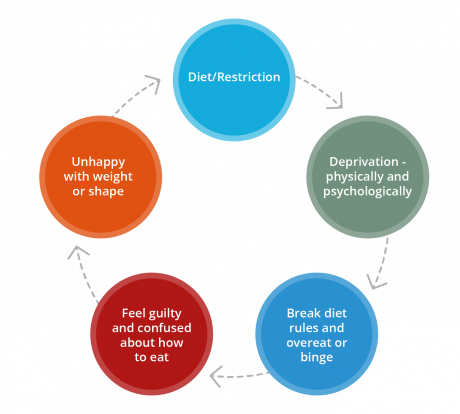

Another very significant risk factor is dieting. No diet in particular is specifically linked with increasing the risk of BED, just dieting in general. Dieting is rooted in restriction of some sort, whether it be restricting a food group (like fats, carbs, or dairy), restricting when you’re allowed to eat (intermittent fasting), or restricting the quantity of food (calorie or points counting). Dieting has been linked with psychological manifestations including preoccupation with food, or as many people may say, “food noise”. Dieting may also result in physical changes that would increase the risk of binge eating. Sporadic eating may increase blood sugar highs and lows, which may increase sugary food cravings. Dieting, or weight loss in general, may also cause a change in the production of hormones, which help work towards homeostasis (balance), in energy intake and ultimately weight. For example, leptin is a hormone that controls our appetite in the hypothalamus; more leptin = less appetite. Leptin is predominantly secreted by adipose tissue (fat). So more adipose tissue, more leptin, less appetite. When we lose weight, we lose adipose tissue, which causes a decrease in leptin, and ultimately, an increase in our appetite. Another example is ghrelin, which is also an appetite hormone. Ghrelin is secreted in the stomach prior to a meal to increase hunger then it is decreased after a meal. When the body is in a caloric deficit, more ghrelin is produced which ultimately increases hunger.

The diet cycle below reiterates how dieting may lead to binge eating, then also adds how the cycle may be maintained through guilt, confusion, and disappointment with self, ultimately leading to more dieting and restriction.

So what are the strategies to get out of this cycle?

Talk therapy is a crucial part of recovery from BED, and there are evidenced based therapeutic strategies that have been shown to help. It is also important, though, that nutrition is being addressed simultaneously. The main nutrition strategies often addressed include:

- Structured eating to ensure regular intake

- Increase the variety of foods eaten

- Reintroduction of foods often binged

Structured eating recommendations from a registered dietitian ensure regular intake and nutritional adequacy. Regular eating patterns that include enough food to meet needs helps break the cycle by avoiding any sort of restriction. They are also necessary as people with BED may have difficulty recognizing hunger and fullness cues due to the disruption in the body’s regulatory mechanisms. Lastly, these recommendations help with digestion as binge eating can often cause symptoms such as heartburn,cramping, extreme bloating and diarrhea. Structured eating recommendations generally include consuming well rounded meals and snacks that contain all of our essential nutrients, and eating every 3-4 hours throughout the day.

Once regular meal intake is reliably occurring, variety can start to be added to the diet. To add variety to the diet, food rules often need to be challenged as do the notions that there are any “good” or “bad” foods. Adding variety also serves as an opportunity to start having more flavor and texture experiences which contributes to satisfaction, and ultimately helps decrease binge eating risk. Variety can be added while still avoiding binge food triggers as needed. For example, if chips are a binge food, then perhaps adding pretzels to the diet regularly could serve as a substitute in the short term.

After adding variety back to the diet, it would then be appropriate to start slowly reintroducing the foods that are most likely to be binged. To continue the previous example, if chips are a binge food, then it may not yet feel safe to bring them into the home. Instead, it may be recommended to do exposure challenges with chips. This may look like buying individual bags of chips regularly to consume. Ultimately, the goal would be to work towards feeling comfortable around chips again so that they can be kept in the home without feeling the urge to binge them.

Those suffering from binge eating disorder, just like those suffering from any other eating disorder, deserve the ability to recover. With the help of an interdisciplinary team including a therapist and registered dietitian, both the psychological and physical effects of the disorder can be addressed.

Resources:

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/eating-disorders#part_2570

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338301/table/introduction.t1

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1471015318303234?via%3Dihub

https://www.waldeneatingdisorders.com/blog/binge-eating-disorder-what-are-the-risk-factors

https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/restricting-sugary-food-may-lead-overeating

https://www.jandonline.org/article/S0002-8223(96)00161-7/abstract